Why Catholicism Makes the Most Sense

I’ve mentioned elsewhere that I’m working on a more extended treatment of my case for Catholicism—for now, here are a few summary points.

I’ve mentioned elsewhere that I’m working on a more extended treatment of my case for Catholicism—including my own conversion story. I’m not quite sure when that’ll be ready for release, but in the meantime, here are a few summary points. That is, some of the points that ultimately led me—once a long-time atheist and secularist—to become Catholic.

I do very much love all my Protestant friends—of which I count many. But I also have to be honest: once I began considering Christianity seriously, Protestantism was, for me, something of a non-starter. Not only because of the positive case for Catholicism, but also because of the problems inherent in the Protestant paradigm as a whole. Again, I respectfully sketch some—though not all—of those considerations here (or at least their general contours). A full, independent investigation is left to the interested reader.

And of course, given yesterday’s news, I can’t help but dedicate this effort to Pope Francis—may he rest in peace.

Why Catholicism Makes the Most Sense

I suppose the simplest statement I can make for Catholicism parallels the simplest case I can make for God: I think it makes the most sense of the widest range of relevant data.

Just as I would say that classical theism is the best (and most relevantly simple) theory for making sense of phenomena like contingency, consciousness, rationality, morality (both moral facts and moral knowledge), the hierarchy of being, the layered structure of reality, religious experiences, near-death experiences—the list goes on—I would contend that Catholicism is the best account of Christianity. Which is just to say: it makes the most sense of the most relevant historical and theological data within Christianity—ecclesiology, sacramentality, institutional authority and continuity, what the Church Fathers taught about schism, baptismal regeneration, merit, and, of course, the biblical data.1

(Not only that, but I’d also argue that the Catholic paradigm of Scripture, Tradition, and the Magisterium is far better supported historically than the Protestant paradigm of sola scriptura. Which is why, I take it, the more sophisticated defenders of sola scriptura don’t even attempt to argue that their paradigm was operative in the apostolic age—because, quite simply, it couldn’t have been. Scripture didn’t just drop from the sky upon Christ’s ascension, after all. It took time—not just for teachings to be committed to writing, but for those writings to be collected, recognized, and assembled into an actual canon.)

Another major reason I became Catholic—perhaps the major reason, apart from the cumulative case—is the need for religious epistemic authority. The purpose of an epistemic authority is to increase our chances of arriving at truth, especially in matters not reasonably adjudicated by our own rational powers. In other words, one accepts an epistemic authority because they believe they’re more likely to form true beliefs (and avoid false ones) by following that authority’s guidance than by trying to figure everything out on their own.

We rely on epistemic authorities all the time, of course. In my tu quoque article, I argued that we can use private judgment to reasonably identify authorities in fields like medicine, while also recognizing that we lack the expertise to navigate those fields entirely on our own. (There are countless other examples, including more mundane ones—like hiring a trail guide for a hike. It’s not only natural, but entirely inevitable, that we rely on epistemic authorities throughout life. Our private judgment can identify competent authorities, but it’s often not well-equipped to operate independently apart from such authorities.)

The same principle applies to religious authority: we can use private judgment to responsibly identify where authoritative teaching is found—especially where it’s obviously needed—without needing to make ourselves the final arbiter of every doctrinal matter.

Clearly, Scripture is not self-interpreting. As

has pointed out, it cannot suddenly grow a face and give you a thumbs-up or thumbs-down to confirm whether your interpretation is correct. Ultimately, within the Protestant paradigm, you are always, as Ybarra puts it, “looping back” to yourself—you alone are the final judge. And that, I think, is a problem, because we are not particularly well-equipped to decipher the meaning of so much of what is recorded in Scripture. Nor, for that matter, are we particularly well-equipped to determine, with any serious degree of confidence, what even counts as Scripture (the canon problem), or how to apply biblical teachings in changing and evolving cultural contexts.In contrast—that is, to sola scriptura—Catholicism offers a living authority (the Magisterium) that can provide guidance on such matters, about including what the boundaries of Scripture actually are. In both theory and practice, this means we can continually loop back to a stationary judge, ultimately achieving adhesion to an arbiter beyond ourselves. Of course, this doesn’t mean adhesion always happens, or happens immediately—sometimes one must loop back multiple times. Nor does it mean the Church always provides instant clarity; in some cases, clarification emerges only after decades or even centuries.

The point is just that the Catholic Church can provide clarity and achieve adhesion in a way that simply isn’t possible within the Protestant paradigm. The difference is one of kind, not just degree.

The problem—the really big problem, as I see it—is that the Protestant paradigm effectively leaves individuals to figure out for themselves matters that are presumably salvific—issues of the highest importance—when, in reality, most people are wholly unequipped for that task.2

And in this sort of situation, private judgment is clearly inadequate, given the massive historical, exegetical, philosophical, and theological complexities involved in discerning Christian doctrine. It is—if I may—aggressively silly to suggest otherwise, at least with any serious degree of confidence (serious enough, for instance, to accuse others of heresy).

On the other hand, one’s private judgment is certainly adequate to identify the Catholic Church as an infallible religious (and epistemic) authority—a crucial difference.3 This is because there are already good a priori reasons to think that God would provide an authoritative Magisterium alongside propositional revelation (as Joshua Sijuwade and others have argued), and the Catholic Church rather easily meets those expectations.

What I mean is: it’s not difficult to discern which Church that would be—since there’s really only one extant ecclesial Christian body that even claims to be an infallible authority and has the relevant historical record.4

Lots more, of course, can (and has) been said about all this; my aim for now is just to point.

OK.

Finally, we should at least briefly consider the need not just for a general living authority, but for a specifically infallible one—since that’s often where people start to get uncomfortable. It is, after all, a peculiarly Catholic claim.

Suppose, then, that we grant that the Church is generally reliable, but not infallible—at least not on essential matters of faith and morals. The moment we do that, however, we run pretty quickly into a problem articulated by John Henry Newman, who offers what is probably the simplest (if not the strongest) reason for accepting infallibility outright:

“In proportion to the probability of true developments of doctrine and practice in the Divine Scheme, so too is the probability of the appointment in that scheme of an external authority to decide upon them, thereby separating them from the mass of mere human speculation, extravagance, corruption, and error, from which they grow. This is the doctrine of the infallibility of the Church.”5

Robert Koons makes essentially the same point:

“Since theology develops over time, building on the settled conclusions reached in the past, if the Church were reliable but fallible, errors would not only accumulate over time but would actually tend to increase at a geometric or exponential rate, each error increasing the probability of further errors. Hence a reliable but fallible Church could not remain reliable for very long.”6

In other words, as soon as one accepts the development of doctrine—as in, at minimum, deeper understanding and clarification of revealed truths, which all Christians do and must (this seems inevitable, given doctrines like the Trinity, Christology, original sin, etc., all of which involve doctrinal development)—Newman’s point kicks in.

Again, much more can (and has) been said on all this, including about the nature of the Papacy and what it actually entails. And it’s worth repeating—because it bears constant repeating—that many objections to Catholicism stem from misunderstandings or misrepresentations of what the Church actually teaches. For a particularly helpful summary, see again Sijuwade’s article The Papacy: A Philosophical Case.7

But I’ll just leave it here, for now.

- Pat

P.S. Or maybe not... there are actually two other quick points I want to make in favor of Catholicism.

First: I think it's generally wise to avoid major error theories whenever possible—essentially, those that claim humanity has, in some large-scale sense, gotten things profoundly wrong.

Take moral anti-realism, for example. It requires a significant error theory: it must explain how we’ve been radically mistaken about something that seems obviously real—namely, moral facts/obligations. Anti-realists argue that evolution instilled these moral beliefs in us, not because they track anything objective, but because they were useful for survival—helping us “have sex and avoid bears,” as the saying goes.

But the problem with embracing such an error theory is containment. How do you confine your being wrong to just that one area, without it spilling over into others—epistemic norms, belief in the external world, etc.?

Once you let in the so-called Darwinian acid, it seems to eat through much more than just moral beliefs. (Though I won’t get into that here; this is a huge debate.)

The point is: if you can avoid committing to a major error theory, you probably should.¹¹

And that brings me back to Protestantism. Because one of the underlying issues in the Protestant paradigm is that it requires a substantial error theory with respect to Christian history. That is, it commits one to the belief that for a significant stretch of time—especially during the medieval period, though even earlier—the majority of Christians, including many saints, theologians, and Church Fathers, got very important theological matters completely wrong.

This would mean that, for centuries, most Christians were fundamentally mistaken about doctrines like the Eucharist, the role of tradition, or the authority of the Pope.

But if we were so wrong for so long, why should we now believe with any confidence that we’re right? And why assume we’re not also wrong about things like the divinity of Christ or the Trinity?

At the very least, this casts doubt on the reliability of Christian theological development—a reliability that every Christian, Protestant or Catholic, must in some way rely on.

My suggestion: Protestantism faces a containment problem, much like the Darwinian acid. It opens the door to radical revisionism and, with it, potentially catastrophic religious skepticism.

Here I’m reminded of a comment posted by Dr. Steven Nemes after his debate with Sijuwade:

“Nemes is not a Protestant.”

Which reformer claimed for himself the right to decide what counts as Protestant and what doesn’t?

“The reformers all believed in the Trinity.”

Martin Luther, John Calvin, and Ulrich Zwingli did. Michael Servetus, Faustus Socinus, and Ferenc David did not.

“Those guys don’t count.”

Why not?

“The Protestant churches all denounced unitarianism as a heresy.”

The Polish brethren and the Unitarian church in Transylvania did no such thing. “Those churches don’t count.”

Why not?

“Because they don’t believe in the Trinity!”

Who is the Protestant Pope who decides what Protestants have to believe in order to be Protestant?

“The historic Protestant churches all affirmed the trinity.” Some of them, and some of them didn’t. And of the ones that did, some of them became liberal and produced many theologians who did not affirm the trinity. I am in this liberal Protestant tradition.

“Liberal Protestantism isn’t Protestantism.”

That’s like saying poodles aren’t dogs because they aren’t beagles.

Just become Roman Catholics if you want a Pope who decides what people can believe and what they can’t! If you don’t want a Pope, then be intellectually honest and allow room for debate and disagreement.

Catholics, by contrast, don’t have this problem.

We can simply say that while doctrine has developed, God’s Church—the mind of Christ—never disappeared, never went totally off the rails. People broke away, to be sure, but the institution itself—authoritative and divinely protected in its essential teachings—was always there. And it’s still here. You can align with it, partake in it, and participate in it today.

If I can embrace a Christian story that doesn’t require me to believe the Church completely collapsed on a mass scale, I’m going to do that (other things equal). And Catholicism gives me exactly that option.

Continuity is a powerful, elegant Christian thesis. It fits the data. It averts religious skepticism.

Second: I frequently detected an obvious double standard at play among Protestants arguing their case—often deployed in an obviously question-begging context. What I mean is this: Protestants often set an extremely high bar for the Catholic to prove their paradigm from Scripture—but in doing so, they already assume sola scriptura is true. This is textbook question-begging as it demands that the Catholic prove their case using the very paradigm that is under dispute. Certainly, the Catholic is under no obligation to play by those rules (even if many of them feel the challenge can be met!)

Yet, at the same time, Protestants do not demand the same level of biblical evidence for their own paradigm.

In other words, if the Protestant insists that Catholics must provide an explicit biblical basis for their authority structure, then they must provide the same for their own paradigm. Yet, Scripture offers no hint of an expected shift to sola scriptura in the post-apostolic age. (Nor would it be useful for the Protestant to claim that their system is more minimalist and elegant; it’s not as if the Protestant simply accepts their position and is open to more—no, they accept their position while rejecting what the Catholic holds. For instance, they don’t just accept that Christ is divine and nothing more about some Pope; they accept that Christ is divine and that He did not establish a Pope. Similarly, they don’t just accept that Scripture is authoritative; they accept that Scripture is authoritative and nothing else is as authoritative, including Tradition or any Magisterium. Probabilistically speaking, "A and not-B and not-C" is just as substantial a commitment as "A and B and C." And as I’ve argued elsewhere, for those concerned about the Catholic ultimately committing one to more dogma—and thus perhaps increasing the likelihood of being wrong—this worry rests on the assumption that Catholicism is false, which is question-begging. Whereas, if Catholicism is true, the worry is unfounded.)

In fact, the opposite is true, at least upon examination of the best historical evidence. The early Church clearly functioned with bishops, councils, and oral tradition for centuries before a finalized canon emerged—precisely the kind of structure one would expect under the Catholic paradigm.

OK, enough!

Ah... not quite.

Bonus 1: I think there are plenty of occurrences that are quite expected if Catholicism is true, but rather surprising if it isn’t: apparition accounts, the sheer endurance of the institution, the lives of the saints, power over demons, the consistency of teaching—especially sexual teaching in today’s culture—etc.

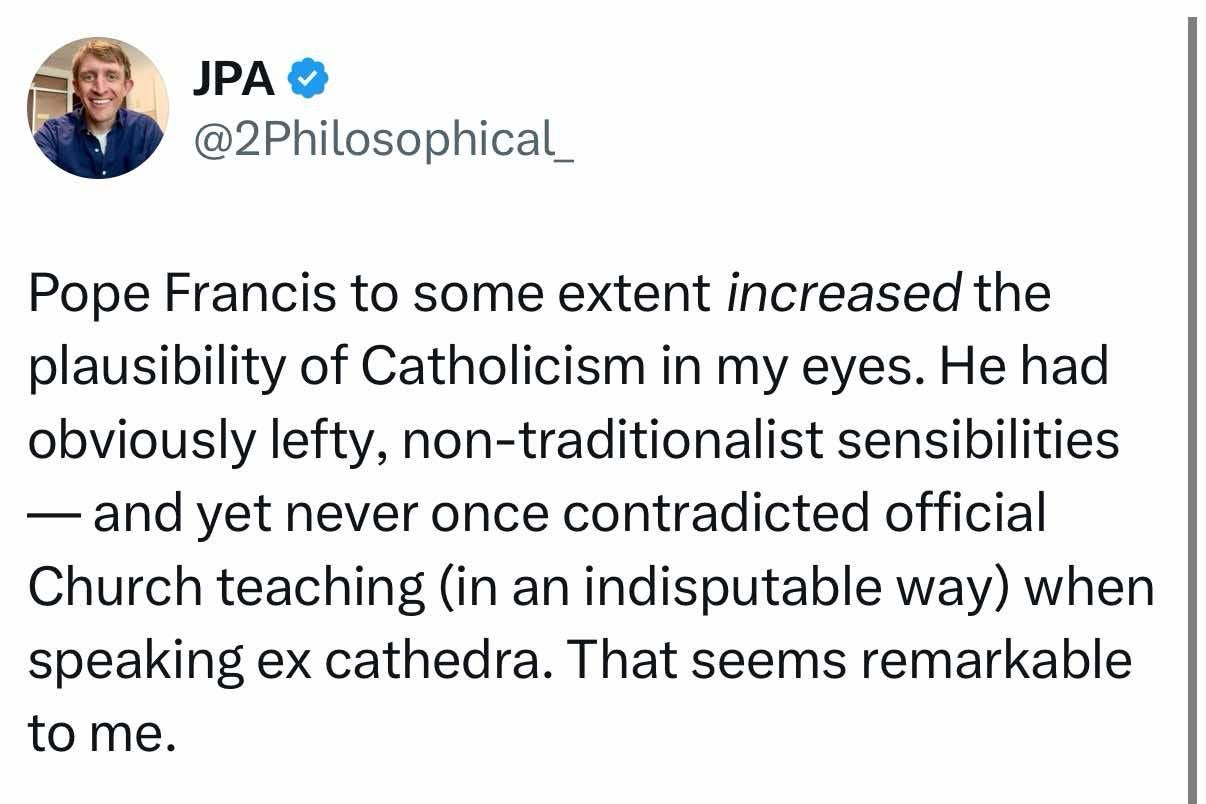

Bonus 2: Not for nothing, but just as I was writing this post, philosopher J.P. Andrew posted the following. I agree with him, of course. I’m not sure what his religious background is—if any—but I agree with him.8

See Brian Cross’s essay in Faith and Reason.

This sort of radical individualism is also, I would suggest, at odds with human nature as social animals, whereas the institutional-communal paradigm of Catholicism is right at home. There’s a wider point here, too, about God working with things according to what they are.

This, I think, is the crux: private judgment may be sufficient to identify an epistemic authority—but it’s nowhere near sufficient to replace one. And once that’s clear, the case for the Catholic paradigm becomes much harder to ignore.

If there were, say, four significant historical churches, each with their own popes, each claiming Vatican I-like infallibility, that would be a real problem—but that’s not the actual world, and I think God has arranged it that way for a reason.

Newman, An Essay on the Development of Christian Doctrine, p. 78.

A Lutheran’s Case for Catholicism, pg. 74.

Another key point Sijuade makes is that a culture-relative revelation—i.e., Scripture—is tailored to the scientific, historical, and theological assumptions of the culture in which it is initially revealed, making its moral teachings immediately accessible and understandable. While this approach offers the advantage of immediate relevance, it presents a challenge when transmitting revelation across different cultures or generations. The original cultural presuppositions may obscure the core message over time, and future cultures may struggle to distinguish between cultural assumptions and theological truths. This limits the cross-cultural and transgenerational effectiveness of revelation. Thus, Sijuade argues that some form of ongoing interpretive authority is necessary to clarify and preserve these essential truths over time and across cultures.

Especially true since—so far as I know—Pope Francis never made any ex cathedra statements.

"A small mistake in the beginning is a big one in the end, according to the Philosopher in the first book of On the Heavens and the Earth." (De Ente et Essentia).

Of course, I think the Protestant would say that Scripture functions as a constant check. And this is, in part, true. Scripture can function as a check, but only when Scripture is read within the lens of Scripture and the Magisterium. Otherwise, it is frighteningly easy to get a text to conform to your background assumptions.